Open data is essential for governments to provide better and more informed public services and to establish transparency and accountability in their decisions. Measures for open data are also suited for combating corruption by promoting openness values around government information. However, making government data available is only the first part of making efficient use of it, the second part is putting it to purpose. In a tour visit organised by SETUP Media Lab, participants from our Integrity and Anti-Corruption course explored Utrecht and discovered open data in action around the city.

Data is all around us, and practitioners at all levels of government have increasingly pushed to make it accessible for the public good. As of now, 25 countries and 65 regions and cities – from the Philippines to El Salvador and Madrid to Taipei City – have adopted the International Open Data Charter, aiming to make government data available to the public by default and promote a culture of openness around information.

In the Netherlands, the use of open data has matured since the Ministry of Internal Affairs first committed to making government information public in the 1990s. Now, there has also been a greater focus on its localisation, with Dutch municipalities using open data in a targeted manner.

As part of our Integrity and Anti-Corruption course, a cohort of professionals from all over the world took part in a study visit organised by our partners at SETUP Media Lab. They guided the group through the city of Utrecht, visiting sites along the way that exemplify how open data can be used by local officials to promote transparency, accountability and good practices for service delivery.

Join us as we highlight some of the locations visited on the tour, each connected to its own open data story.

At a skate & callisthenics park: do wealthier people have more access to sports?

Their first stop on the tour was at a local sports facility. Over time, researchers have established that lower-income individuals report lower levels of health than those with higher incomes. Several factors can play into this, like the quality of foods available to them, or the funds needed to access gyms and sporting programmes. Overall, time, money, and location could prevent low-income individuals from engaging in exercise regularly. Wondering if there was a way the municipality could alleviate the discrepancy in health between rich and poor citizens, researchers narrowed the problem to one variable to start: location. To further explore the problem they began with this question: do people with a higher income, who report higher standards of health, have more sports facilities in their direct neighbourhood? If so, then the municipality could better citizens’ health in less wealthy neighbourhoods by increasing the amount of sports facilities in their vicinity.

Their first stop on the tour was at a local sports facility. Over time, researchers have established that lower-income individuals report lower levels of health than those with higher incomes. Several factors can play into this, like the quality of foods available to them, or the funds needed to access gyms and sporting programmes. Overall, time, money, and location could prevent low-income individuals from engaging in exercise regularly. Wondering if there was a way the municipality could alleviate the discrepancy in health between rich and poor citizens, researchers narrowed the problem to one variable to start: location. To further explore the problem they began with this question: do people with a higher income, who report higher standards of health, have more sports facilities in their direct neighbourhood? If so, then the municipality could better citizens’ health in less wealthy neighbourhoods by increasing the amount of sports facilities in their vicinity.

To answer their question, researchers used three different, openly available data sets: health information from all the neighbourhoods of Utrecht, income data of all the neighbourhoods of Utrecht and the locations of Utrecht’s sports facilities. But what they found, in the end, was surprising: Utrecht’s sports facilities were evenly spread among all its neighbourhoods. Creating more sports locations, then, would probably not be an efficient solution to increase health in less wealthy neighbourhoods. Although the study did not provide a positive correlation, the use of open data allowed for a better-informed decision around a public health problem.

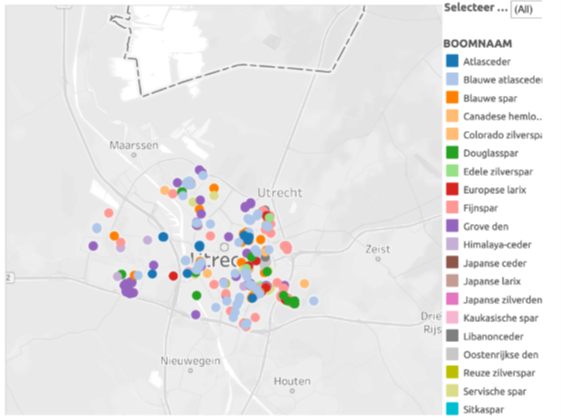

At the Old Canal: what kind of trees are there in the city, and where are they located?

Although Utrecht has plentifully green areas, it ranks as one of the least green cities in the Netherlands. At the park around the Oudegracht, or old canal, they learned that Utrecht’s municipal government has started keeping track of all public trees in their city. Each tree is given its own ID, location, type and year planted, all stored in an open data set. This data file can be used by officials and activists to ensure urban biodiversity by taking stock of what they have available. Even more, as our tour guide showed, simple data sources like these could even give way to local tourist attractions. For instance, they used the data on these trees to make a map of the ten oldest trees in Utrecht, offering a quaint cycling tour around Christmas.

Although Utrecht has plentifully green areas, it ranks as one of the least green cities in the Netherlands. At the park around the Oudegracht, or old canal, they learned that Utrecht’s municipal government has started keeping track of all public trees in their city. Each tree is given its own ID, location, type and year planted, all stored in an open data set. This data file can be used by officials and activists to ensure urban biodiversity by taking stock of what they have available. Even more, as our tour guide showed, simple data sources like these could even give way to local tourist attractions. For instance, they used the data on these trees to make a map of the ten oldest trees in Utrecht, offering a quaint cycling tour around Christmas.

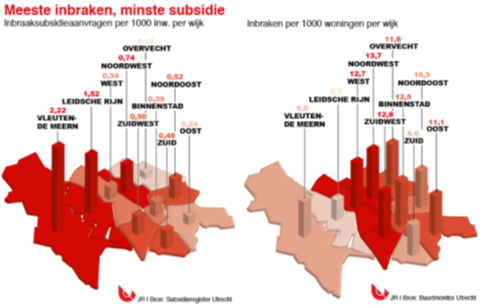

At the Buurkerhof: who requests the most burglary prevention subsidies?

At the Buurkerhof, a square near Utrecht’s towering cathedral, our tour guides explained how the municipal government offers subsidies to individuals taking extra measures to prevent burglaries, like upgrading older locks to better secure their homes. This municipal initiative was meant to reduce theft around the city by making citizens security-aware and making it easier for them to enforce home safety through municipal subsidies. But did citizens actually make use of the offered subsidies? Through data sets that showed municipal subsidy information, neighbourhood crime rates, homeownership and income levels, a team of researchers made a compelling discovery: most of the money from municipal subsidies went to neighbourhoods with already less crime, and with higher incomes and home-ownership rates. They found that neighbourhoods with more theft requested fewer subsidies from the municipality, indicating a mismatch in communication or simply trust between the municipality and portions of their citizenry. Open data like this could make way for municipal programmes to address the situation.

At the Buurkerhof, a square near Utrecht’s towering cathedral, our tour guides explained how the municipal government offers subsidies to individuals taking extra measures to prevent burglaries, like upgrading older locks to better secure their homes. This municipal initiative was meant to reduce theft around the city by making citizens security-aware and making it easier for them to enforce home safety through municipal subsidies. But did citizens actually make use of the offered subsidies? Through data sets that showed municipal subsidy information, neighbourhood crime rates, homeownership and income levels, a team of researchers made a compelling discovery: most of the money from municipal subsidies went to neighbourhoods with already less crime, and with higher incomes and home-ownership rates. They found that neighbourhoods with more theft requested fewer subsidies from the municipality, indicating a mismatch in communication or simply trust between the municipality and portions of their citizenry. Open data like this could make way for municipal programmes to address the situation.

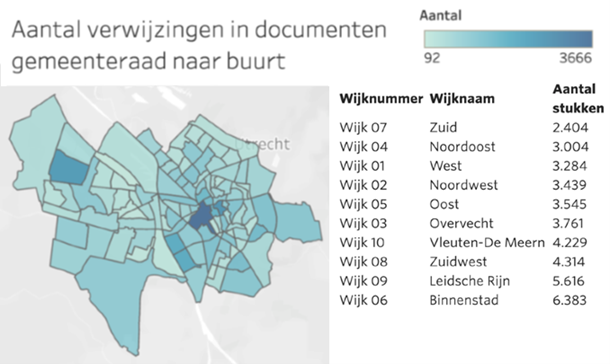

City hall: which neighbourhoods get the most attention from the city council?

The Utrecht municipal government aims to represent the interest of all its citizens equally, but any local activist, official, and citizen can use open data to measure results for themselves.

The Utrecht municipal government aims to represent the interest of all its citizens equally, but any local activist, official, and citizen can use open data to measure results for themselves.

Stopping at the city hall, our tour guides asked a straightforward but crucial question: which neighbourhoods get the most attention from Utrecht’s city council? By analysing documents readily available at the council archives, Setup’s tour guide and researchers put the data through an algorithm that counted each time a neighbourhood was mentioned in the council’s agenda. They found that Utrecht’s city centre was mentioned the most, while many of the city’s outer neighbourhoods with issues of their own appeared less discussed. By allowing this information to be made public, Utrecht’s city council has empowered its citizens to hold it accountable, a measure that ultimately gains trust among citizens and opens the door for cooperation and better (and more equal) representation in the future.

Tour guide: Sebastiaan ter Burg, one of the DataDUICers: a group of local volunteers that do civic research on basis of local open data and publish their conclusions in a local newspaper. He is also a board member of Open Nederland, an association that promotes openness and the use of open licenses like Creative Commons. He was also one of the initiators of UtrechtOpenData.org.

Join our Integrity and Anti-Corruption Course! Interested in the drivers of corruption, their impact on development & how to promote a culture of integrity? Sign up for our Integrity and Anti-Corruption course, taking place annually. In 2022, the course will be held between 5 and 16 September. Please note that the deadline is 29 July 2022.

Related courses

We offer a diversity of courses throughout the year. Here are several other courses you might like.